How We Started Snaddering

Tuesday the 28th of September 2021

I made friends with Kevan over the idea to make a book that was a board game. Or a book full of board games. A board game book. He was a game designer and I made books, and I loved board games.

I had to admit that I found actually playing board games incredibly stressful, though.

"Wait, how can you love them if you don't like playing them?"

"I like the idea of them. But learning and teaching rules is stressful."

"How about making them up?"

A year later, we had a ritual in place. We'd be sitting together in some cafe or pub, and then decide to make up a game and play it. We called it snaddering, because at the very beginning we'd started by drawing a game of snakes and ladders — a game so simple and entirely luck based that I used to play it with my dog as a child and lose half the time, the game that everyone starts with when they want to make up their first game. If you add branches to the paths, you add choice. Then you add rules.

"Let's snadder a game."

"All right. What about?"

"Underwater welding. I read that that's the most dangerous job there is."

"Is it?"

"I don't know. I'm stressed. It seems right."

"All right. I'll draw the board."

"Here, this bottlecap is a shark. — What did you just write there?"

"If you're on this square, someone has to come rescue you in the next three moves or you drown."

"So this is co-operative?"

"Sure."

"All right. We win if everyone lives to lunch time."

"All right. How do the sharks move?"

"Really fast."

This is how it worked:

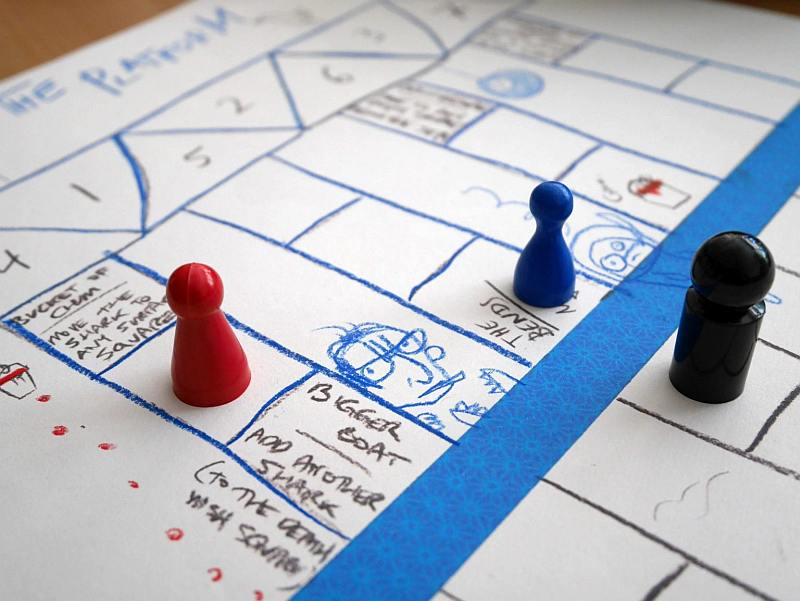

One of us drew a board, branching paths of squares.

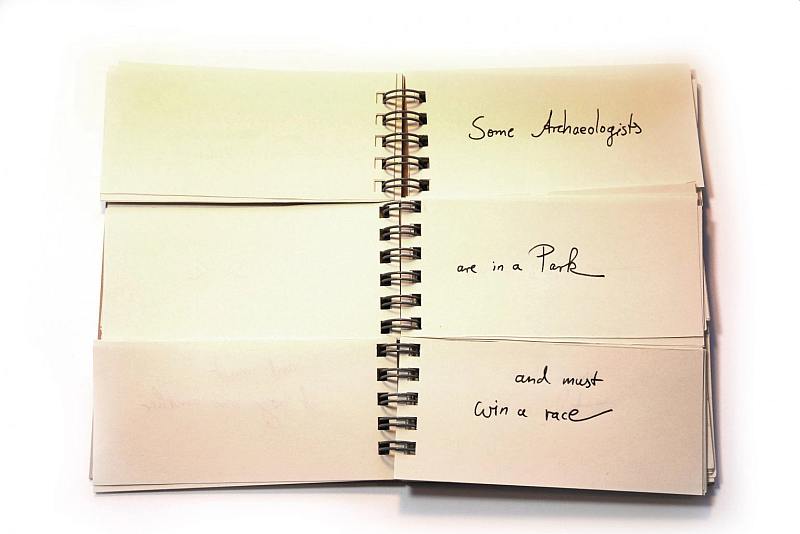

We decided who we were, where we were, and how to win. Sometimes we used a random generator to decide for us: We are nuns in a supermarket trying to uncover a secret. We are cowboys on a distant planet trying to survive.

After that, we agreed some very few rules for the whole game — usually one basic mechanic like hidden identities or collecting tokens. Then we started scribbling small local rules in the squares, doodling some scenery, adding tokens or cards as needed, whatever came to mind. The squares did not have to be clever. No elegance was expected. Ideally, they should interact with the main rule or rules somehow, but they did not have to. The general idea was to just accept, as in the established rules of improvisation (which of course includes the right to reject anything that anyone finds insulting or just really does not want to do).

When it seemed ready, we played.

No one lived to lunch time that day we were underwater welders. And I did not manage to find the traitor on the space station another day. But I was the best wildlife photographer in the game about a magnificent bird of paradise folded from a chocolate wrapper.

A snaddered game, so it emerged, was a kind of a paper brain filled with little thoughts that made unexpected patterns when played. Simple and complicated ideas were of the same importance in such a pattern. Chance quickly turned into strategy, naturally.

It took us five years to test the system, work out how to teach other people how to snadder, turn it into a book and find a publisher.

We found out quickly that game designers tended to snadder the worst games, because they insisted on thinking through and testing every step. That's a good habit in game design, but forbidden in snaddering.

No testing. Just scribbling. Letting chaos and order run together. Improvising. If in doubt, accepting ideas.

People who had no idea how board games should work made the most enjoyable games, and often surprisingly elegant ones, too.

When we combined skill levels wildly, incredible things happened. There was a memorable game that involved a zoo run by a wealthy cat who drove around in a car, trying to stop players from liberating the animals. The elephant was hard to carry. The crocodile could be inflated, if you managed to sneak it to the gas pipe. It was one of the most joyous games I ever saw played, made by people who never met before.

We weren't sure that children could snadder, but over and over they turned out to be incredibly good at card management, and the introduction of bold visions that the group quickly turned into working rules. They also turned out to be good at making everyone make lots of cards, parts, and bills of money.

A lot of best laid plans fell away. Amazing, neat things that no one had expected emerged when the games were played.

So, is this a good way of designing board games?

It is a brilliant way of designing the one board game that the people who are right here and now want to play. It can be about a movie you all watched. You can just decide, and make it. Sometimes it will be a mess. Often, it will be amazing to see all those things you threw at the board connect up and come to life as a story you didn't expect — every board game is a story, after all. In a way, snaddering is telling a story together via the making and playing of a board game.

And yes, sometimes the structures that emerge this way are neat enough to be developed further, inspiring neat board games. But that's not the point.

The point is... you make and play a game with your friends, about anything you like, all in the space of an hour, and you never need to learn the rules. You make them.

This piece of writing was originally commissioned for the 2021 Jump Festival.

Board Games To Create And Play is a book describing the snaddering game design system, with 58 blank tear-out boards and dozens of suggested rules to try (from barricades and secret identities to card-based movement and worker placement).

You can buy it from sites including Bookshop.org, Amazon UK, Amazon US, Barnes & Noble, Foyles, Hive UK, The Ludoquist and Waterstones.